Selected Exhibits

Tripods are very particular objects for the cult of Apollo. According to the myth, Hercules went to the oracle of Delphi in order to ask what to do in order to be expiated from the murder of Iphitos. The oracle did not want to give him an omen. Then, the hero was enraged and he grabbed the tripod on which the Pythia sat in order to pronounce her oracles. Apollo tried to prevent him and this resulted in a fight between the god and the hero. Finally, Zeus had to intervene in order to end this quarrel. This tradition, however, inspired the iconographers, whereas the tripod emerged as a fundamental cultic object. In the Geometric period, the tripods were fastened to the cauldrons they supported. In the Museum of Delphi there are fragments of such tripods, most distinctive of which is the one with a ring-shaped handle.

In Homer’s poetry there are frequent mentions of these objects. They appear to be precious gifts for the guests, as in the case of the Phaeakes, who offered a cauldron and tripod to Odysseus.

Our guest has already packed up the clothes, wrought gold, and other valuables which you have brought for his acceptance;

let us now, therefore, present him further, each one of us, with a large tripod and a cauldron. We will recoup ourselves by the levy of a general rate; for private individuals cannot be expected to bear the burden of such a handsome present.

Odyssey, 13.10-15 [tr. S. Butler]

At the end of the Geometric period an innovation is introduced: the tripds are detached from the large bronze cauldron, which is now placed on them. In the Museum there is a distinctive specimen: on a fine, bronze tripod standing on cast legs, lied a large globular cauldron. On its lip there are developed heads of griffins and lions, as well as winged female figures, possibly sirens. These creatures originate from the Middle East, whereas the technique of casting followed by hammering also alludes to oriental workshops.

A usual method for the decoration of furniture and wooden objects were the inlayed tiles with decorative or narrative character. These tiles could be made of metal (usually copper but also gold and silver as well) or even of ivory. In the Archaeological Museum of Delphi are exhibited both ivory tiles (in the hall of the golden-and-ivory statues) depicting mythical creatures as well as bronze tiles representing known mythological scenes.

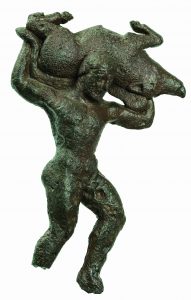

A distinctive one presents the depiction of Hercules’ prowess in catching the Boar of Erymanthus. Eurystheus, king of Tiryns, had asked from Hercules to capture alive the boar that Artemis had offered as present to Erymanthos, because the wild beast destroyed the crops and killed other animals with his tusks. Even the Centaurs of the forest of Pholoe, in eastern Helia, were annoyed by his activity. Hercules managed to capture the boar using a decoy and approaching it from the side. After tying it up, it transported the beast to Eurystheuus, who hid in a jar, terrified. The event was probably considered amusing by the Archaic period artists, who have depicted it on red-figured (e.g. Oltos amphora, 510 B.C., Louvre) and black-figured (e.g. Amphora from Vulci, ca 550 B.C, British Museum). The feat is also depicted on the metopes of the temple of Zeus of Olympia, towards the mid-5th century B.C. This particular example from the Museum at Delphi is the only one known in bronze and dates to the second half of the 6th century B.C. Equally amusing was perhaps the incident of the escape of Ulysses and his comrades from the cave of the cyclops Polyphemos, which constitutes the theme of the second bronze tile: Ulysses or one of his companions is depicted hanging from the belly of a ram in his effort to escape, It is possible that this tile was matched by others depicting the blinding of Polyphemos or other incidents of the Odyssey.

Kleovis and Viton or the Dioscuoi

The two monumental archaic statues were discovered during the archaeological excavations of 1893-4 close to the Treasury of the Athenians. The two yougnmen, probably originally standing one next to the other, are naked, in the kouros type, and look very much alike. Their left foot is stepping forward, whereas their hands are bent at the elbows, touching the thighs and with tightly closed fists. The body and the anatomic details are rendered in a dynamic style. The hair form spiral curls over the forefront and hang in wavy tresses on the shoulders and the back. The large, almond-shaped eyes are crowned by high eyebrows, whereas the face bears an archaic smile. They wore sandals, of which the high soles are discerned. The figures step on different stepping stones but were standing on the same pedestal. According to the inscription partially preserved on the stepping stone of one of the statues they were made by the Argive sculptor Polymedes and constituted an ex voto of the Argives to Apollo. The date suggested is ca. 580 B.C. They are considered a typical specimen of the archaic sculpture of the Peloponnese.

Identification

Formerly, the statues were identified with Kleovis and Viton, sons of a priestess of Hera originating from Argos. According to an ancient tradition, recorded by Herodotus, the two brothers took the place of oxen and dragged their mother’s chariot to the sanctuary of Hera, taking their mother there on time fo the celebration of the Heraea. In return, she asked the goddess to reward them with the best thing a man would ever desire; Hera bestowed on them a calm death in their sleep.

A more recent interpretation, however, based on a careful reading of the inscription FΑΝΑΚΩΝ, i.e. “the Kings”, led to their identification with the Dioscuroi, sons of Zeus and Leda and siblings of Helen of Troy. Castor and Pollux were honoured as “Anakes” in Argos.

No matter what their actual identity is, however, their features are typical of an argive workshop. The torso and arms are rather short, whereas the breast is lifted up and the thorax is marked by an incision. The head is almost cubical and the broad face is flanked by curls reminging of the daedalic statues. The whole composition is “heavier” and sturdier than in the works of the attic and ionic workshops.

Among the inscriptions covering the southern wall of the Treasury of the Athenians, which preserve mostly honorary decrees for citizens of Athens, stand out two inscriptions which attracted the attention of the epigraphists, since it was evident that they recorded poetic verse. A more careful examination proved that they were two ancient hymns to Apollo, out of a total of about fifty known similar hymns from Ancient Greece. The examination of these hymns in relation to other inscriptions from the archaeological site of Delphi proved that the paeans were composed by the singer Athenaeus, son of Athenaeus, and the musician Limenius, son of Thoinos. The hymns were composed on the occasion of the Pythais of 128 B.C., the ritual procession of the Athenians towards Delphi. We know that the performance of one of the two hymns was awarded a prize.

Between the lines of the verses are discerned musical symbols, which have been interpreted by the experts thanks to a treatise by Alypius, a musicographer of Late Antiquity (3rd century A.D.). The first paean consisted of four stances, of which three are extant. The second paean was much larger: it had nine stances and ended with a “prosodion”, i.e. a jubilant finale.

The subject of the paeans is naturally related to various events from the life of the god, such as his birth, his coming to Delphi etc. The god’s contribution to the fight against the Galatians is also hailed.

These hymns were thoroughly examined by musicologists and there have been many efforts to perform them with replicas of ancient musical instruments. The first time that they were performed was in 1894, one year only after their discovery, during the international athletic convention for the establishment of the Olympic Games.

In antiquity, as is often the case nowadays, votive offerings to the gods were considered sacred and thus it was forbidden to sell or transform them. The ex-vottos which were destroyed by a natural cause or which, for some reason, were considered redundant, were usually buried close to the sanctuary. This is what happened probably in the mid-5th century, when a fire destroyed several precious ex-vottos which were then buried in a dump along the Sacred Way, opposite to the Halos.

Some of those probably constituted a gold-and-ivory group depicting the Apollinian triad, namely Apollo, Artemis and Leto. The scholars have related these finds to the sumptuous ex-vottos of Kroesus, king of Lydia, which Herodotus so eloquently describes. This identification is however uncertain; the only certain fact is that the works are magnificent creations of the mid-6th century B.C., coming from workshops in Ionia, or, to a certain extent, Corinth.

Apollo bears the distinctive mild archaic smile. His hair is made of gilded silver, whereas the two broad curls flanking the head and falling on the shoulders are made of a lead of gold. Only the front part of the feet is preserved, as the rest was covered by the garment. The god held in his hand either the gilded silver bowl or the silver cup displayed in the same window case. The work has been attributed to a Corinthian workshop, along with some of the miniature ivory tiles with relief decoration, which probably decorated the back of the god’s throne. On one of those tiles is depicted a scene from the Argonautic campaign: the sons of Voreas, Zythes and Kalais, persecute the Harpyiae who tormented the soothsayer Phineas, and, in exchange, he gives them advise on how to reach Kolchis. Another remarkable scene from the fragmentarily preserved tiles is that of the departure of a warrior on a chariot.

The sweetness in the expression of Artemis, who bears a golden tiara and rosettes in the place of earrings, points out to the Ionian art, probably of Samos. Two large rectangular golden leaves probably ornated the garment of the goddess. They were decorated with depictions of real and mythological animals: a gazelle, a lion, a bull, a deer, a pegasus, a griffin, a sphinx. As in the case of Apollo, the eyes and eyebrows were inlayed. To the same statue probably belonged the left hand with golden bracelet. Apart from the third large head (of Leto) are depicted also parts of other statues. Furthermore, additional golden decorative elements are preserved, among which stand out the tiles with depictions of Gorgo, Pegasus and griffin, as well as rosettes, anthemia and floral items. The group is completed with leaves of gold in the form of curls, parts of garments, tiaras and a necklace with lion heads. In the same window cases are depicted more finds from this dump, such as four bronze sphinxes on Corinthian capitals, parts of a flute made of bone, parts of a gilded silver bowl (phiale), bronze handles of cauldrons, two of which are in the form of a siren with open wings, a base of a bronze incense burner (it bears an inscription which has been related to Kroesus), several tiles made of bone which decorated a wooden furniture or item, two clay sphinxes opposing each other, three clay female heads as well as several bronze arrow heads and iron spears’ tips.

Among the relatively few pottery exhibits in the Museum of Delphi counts a cylix with a white background and a depiction of Apollo; it was found in a dump where votive offerings from graves had been deposed, when the latter had been cleansed. It is a magnificent work of an attic workshop. Inside the cylix is depicted Apollo with an elaborate hairdo and a laurel wreath on his head, sitting on a camchair, the legs of which end up in lion’s paws. The god wears a white chiton, a red himation (cloak) and sandals. A seven-stringed lyre is attached to his left hand with a red stripe, whereas with his right hand he pours a libation out of a shallow bowl decorated with patterns in relief. Opposite the god is rendered a black bird, for which several explanations have been offered: it is identified either as plain oracular bird or as a crow which brought to Apollo the message that his beloved Koronis, daughter of king Phlegyas, was getting married. This exquisite work dates to the decade 480-470 B.C. The depicted scene evokes in a wonderful artistic manner the verse from the second hymn to Apollo found inscribed on the southern wall of the Treasury of the Athenians: “Sing for the gold-haired Pythios who aims far with his bow and arrow and plays nicely the lyre”.

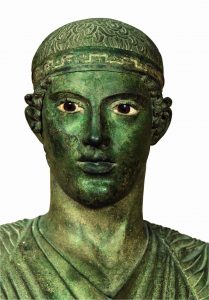

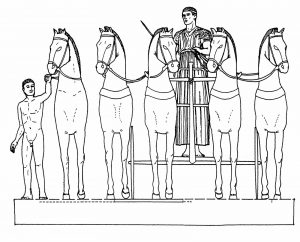

The last gallery of the museum of Delphi shelters its most magnificent exhibit, namely the Charioteer from the ex-voto of Polyzalos, tyrant of the Sicilian city Gela. Polyzalos is considered to have won the chariot race at the Pythian Games of 478 or 474 B.C.; it has been suggested, however, that the ex-voto honours the victory of his brother, Ieron, in 470 B.C., who had also won at the Olympic Games, having dedicated another similar ex-voto there. Despite the contradicting views, it is almost certain that the complex, consisting of a chariot drawn by four horses, the Charioteer and two stable boys, was made to be looked at from the front and left sides, as it was placed on the right side of the Sacred Way, along the part where the road is particularly steep, just before the temple of Apollo. It is also almost certain that the two stable boys were on foot, leading two horses on the right and left sides of the chariot. In a separate window case is displayed the hand of one of them with part of the bridle and parts of the horses. The complex was probably destroyed by the earthquake of 373 B.C.

The Charioteer, of whom only the left hand is missing, wears a long chiton with rich and evenly spead out drapery, tied high, under the breast, with a belt which folds at the back. In his right hand, apart from the preserved bridles, he was also holding a whip. His naked feet step firmly on the ground and are rendered in full detail, which makes one think of the bronze sculptor Pythagoras from the city of Rhegion (who originated from Samos); Plinios used to write about him that he could render even the veins under the skin.

The Charioteer’s head is broad, whereas the youthful and oval face is characterized by strict lines on the nose and the eyebrows. The lips are covered by a leaf of reddish copper and at the back, in between the fleshy lips which lay ajar are vaguely discerned four silver teeth. His eyes are inlayed with white enamel for the bulb, brown and black stone for the iris and the pupil. The gaze is filled with moderate intensity, simplicity and victorious serenity. The hair is rendered with incisions more than in relief and they are held by a broad band with a maeander made of silver and copper. The entire statue is vibrating with a slight helicoid movement to the right.

Apart from Pythagoras, the Charioteer has been also related to the work of Critias or Kalamis, but the existing data do not allow a certain linkage to any of the well-known artists. The only certain thing is that it constitutes on the of masterpieces of Greek sculpture, with features which make it a deeply human and spiritual work, evoking a charm which touches the roots of the western civilization and the deepest parts of the human soul.

It is for this reason that the news for its discovery during the “Grande Fouille” spread throughout the universe, causing a thrill beyond the purely scientific interest.

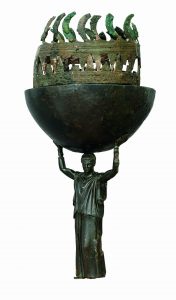

In a separate case in the middle of room 9 is displayed a magnificent bronze incense-burner. It has the form of a peploforos holding the hemishperical body of a cauldron in which the incense was burned.

The female figure wears the doric peplos and a head-cover called “kekryphalos” in the form of a net which holds her hair tied up. She leans on her right leg, whereas the left one is lifted, ready to walk. Her face is tuned towards the right hand. The front side is very elaborate, whereas the back side is coarser and simpler. Her arms are raised in order to hold up a bronze cauldron, where the incense was placed. A perforated cover, now lost, was placed on the rim in order to leave the smoke from the incense disperse.

The style reminds of peploforoi from the museum of Olympia.

It was probably produced in a workshop of Paros around 460-450 B.C., although some views suggest that it comes from a local workshop of Delphi or of some city on the Corinthian Gulf. It has been found in the dump of the Sacred Way, along with other bronze items and several precious ex-votos.

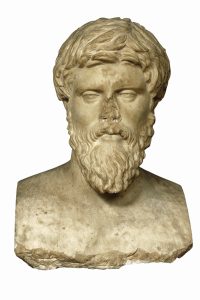

At the exit from the museum there are two exhibits which have been related to the most renowned priest at Delphi, the famous historian of the 1st-2nd century A.D., Plutarch of Chaeronea. Plutarch was born into a local elite family of Boeotian Chaeronea and received excellent education, initially by his grandfather Lamprias and then in philosophical schools of Athens. He rose to local political offices in his hometown; later on Mestrius Florus, a prominent Roman who attained the rank of proconsul of Asia, among other offices, became his patron. Αfter travelling extensively and rising in the Roman hierarchy of offices, Plutarch returned to Chaeronea and then assumed the priesthood in Delphi, where he passed the last 30 years of his life.

The head of a philosopher dating to the 2nd century A.D. had formerly been identified as a head of Plutarch. The man, although bearded, is depicted in a relatively young age. His hair and beard are rendered with bulky parts and fine incisions. The gaze is deep and pensive, due to the heavy eyelids and the incised iris and pupils of his eyes.

Next to the portrait is preserved a fragmentary hermaic stele which was probably crowned by a portrait of the writer and priest from Chaeronea. The portrait is no longer extant, its inscription, however, runs: “Delphi dedicated [this] to Plutarch from Chaeronea, abiding to the command of the Amphictyons” (Syll.3 843=CID 4, no. 151).

Apart from his duties a priest, Plutarch’s literary work is also partly related to Delphi and the sacred rites. Such works are the “On the E of Delphi”, “Why Pythia does not now give oracles in verses”, whereas his most renowned work, namely the “Parallel Lives” were written during the last twenty years of his life, while he lived in Delphi.

On a space above the epigraphic portico of the Museum of Delphi, which reaches the height of the first floor of the museum, is exhibited a mosaic floor from the early Christian basilica of the first half of the 6th century A.D., discovered in 1959 in the village of modern Delphi.

It is richly decorated and combines geometric, floral, animal and anthropomorphic patterns as well as symbolic depictions. The canvas of the mosaic is divided in compartments where several autonomous themes are developed: fish and other maritime beings, birds, wild and tame animals, anthemia, vases, a young shepherd. Along the central nave is preserved a part of a dedicatory inscription as well as a round medallion with a panther devouring a deer, surrounded by peacocks and eagles with spread wings. In the squares of the corners there are young figures holding a canister with fruit and a bunch of crops, which are personifications of the seasons. The mosaic bears an inscription running ΚΑ[ΛΟΙ] ΚΑΙ[ΡΟΙ] (Good weathers).

Stylistic analysis has proved that it was the work of an important mosaic workshop.

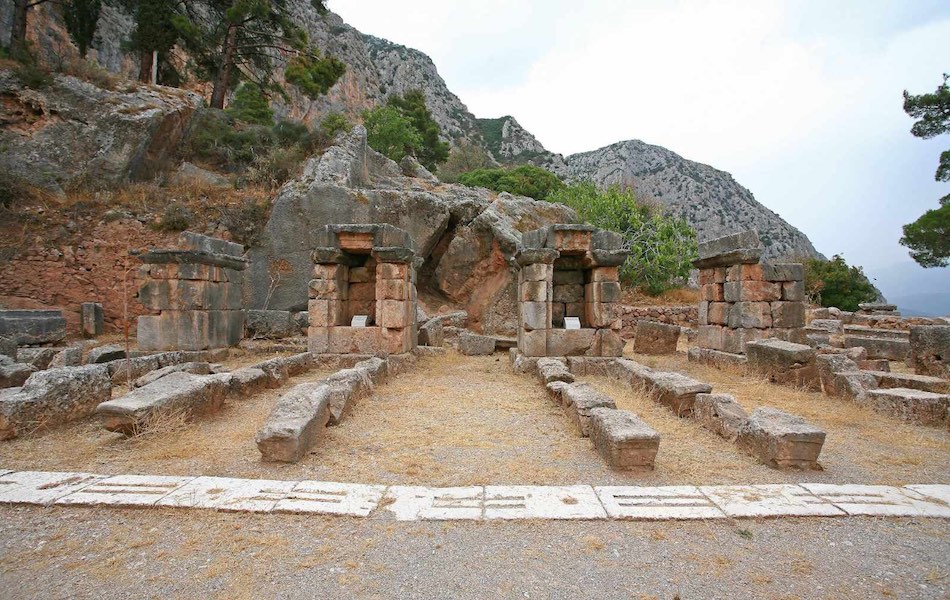

The sculpted decoration of the Tholos in the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia constitutes not only an element for dating the enigmatic monument in ca. 380-370 B.C., but also one of the landmarks of late classical sculpture and its study. Unfortunately the sculptures had been detached already in Late Antiquity. It took decades of studies and conservation works in order for the scholars to reach some conclusions and present the fragments in a more comprehensive way. According to them, the exterior metopes of the building bore representations of Amazonomachy and Centauromachy, whereas the internal frieze probably bore scenes of the heroic deeds of Hercules and Theseus, although this is not certain.

In terms of style, the figures on the exterior metopes are rendered in high relief, with intensive movement and plasticity, which reminds of the architectural sculptures of the Asclepieion of Epidaurus. The torso of an Amazon, displayed in the Museum of Delphi, although fragmentary, is very impressive with its sense of movement and the garment details. The torso is slightly twisted, in order to stress the sense of movement, evident on the upper part of the thighs and in the left hand, which must have been raised. The figure wears a himation with very delicate drapery, attached to the waist with a thin band. A second band crosses under the breast.

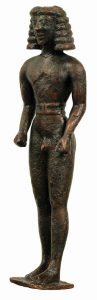

One of the most important exhibits of the Archaeological Museum of Delphi is the daedalic figurine of Apollo. Daedalic art dates to the early archaic period and was named after Daedalus, a mythical figure, inventor and mechanic, who is reportedly the first one to have made statues in natural height, moving in a natural way. The term “daedala” was used also to denote the wooden talismans in antiquity. Daedalic art was developed initially in Crete in the 7th century B.C. and then particularly in the Doric cities and areas. Its main feature was that it followed Geometric precepts, although the forms are rendered in a more plastic way. The figures are frontal, hands stuck on the thighs, whereas the hairdo is formed in horizontal zones reminding of a wig (layered wig).

The naked male figure of the Museum of Delphi has a slightly protruding left leg and his hands with the fists tightly closed are touching the thighs. The waist is thin and surrounded by a metallic belt, whereas the chest is robust and clearly traced. The back is almost flat, apart from the indentation along the spinal cord, which becomes deeper at the lower part. The face is triangular with intense lips, small pointing nose, eyes placed far from the eyebrows and from one another. The hair is combed in the typical style of “layered wig”, in five layers plus one covering the head-top.

The figurine constitutes a precursor of the kouroi made of stone, like those displayed in the museum and identified with Kleovis and Viton or with the Dioskouroi.

Daedalic art in general became particularly widespread in the second half of the 7th century B.C. and then receded once the archaic sculpture and its local “schools” developed. Among the renowned exponents of the same style are the “Lady of Auxerre”, now in the Louvre with provenance probably from Eleutherna, as well as the statue of Nikandre from the National Archaeological Museum of Athens (which is much larger) as well as several figurines from Delos, Eleutherna and Gortyna.

MUSEUM OF DELPHI