The Historical Evolution of Delphi

The role of the Sanctuary during the Second Colonization

The earliest structures associated with the worship of Apollo date back to the late 7th c. B.C. However, votive offerings which came to light in Delphi allow the conclusion that the sanctuary attracted pilgrims even from remote lands, already since the end of the 10th century B.C. The growth of the sanctuary is interwoven with two factors that shaped the social and economic evolution of Greek society: colonization (especially the so-called Second Colonization of the 8th-6th centuries B.C.), and the social and political reforms within the Greek cities, especially the tyrannis.

The sanctuary of Delphi played an important role in the establishment of the Greek colonies. It is believed that before each mission for the foundation of a colony the city would send an embassy to the sanctuary of Delphi. It is possible, however, that the metropolis itself, i.e. the city from which the colonists originated, had already decided upon the foundation of a colony and then requested approval of the process. In any case, before attempting to establish a colony one would consult Apollo. The oracle was addressed personally to the colonist and was accompanied by a mandate based on which the latter would take on various offices such as that of the king, the religious leader, the military leader and the legislator. The sanctuary continued to monitor the development of the colonies even after they were established. Indeed, in times of social crisis, it would recommend a person to intervene as a judge and restore order. Such was, for example, the case of Demonax from Mantineia who was appointed as katartester (mediator judge) at Cyrene.

The role of the Sanctuary in the sociopolitical developments within Greece

Throughout the Archaic period the Delphic sanctuary was continuously active and involved in the sociopolitical changes, especially those related to societal organization. Sparta maintained very close ties with the Oracle. Despite current doubts concerning Lycurgus and the reforms attributed to him, it is certain that, even since the time of the poet Tyrtaeus (late 7th century B.C.) the role of Delphi in these profound changes had been significant (Her. 1, 65; Plutarch, Lycurgus 29).

There seems to be a close connection between Delphi and tyranny given the fact that in many cases the priests supported the tyrants. The prophecy of the Oracle regarding Cypselus as the future tyrant of Corinth is a characteristic story delivered by Herodotus (5, 92). Cylon enjoyed similar support in his attempt to become tyrant of Athens, but failed because he did not interpret the oracle correctly (Thucydides 1, 126, 5). At times, however, the sanctuary opposed tyranny, as in the case of the Orthagorids at Sicyon (Her. 5, 67).

But as soon as tyranny had served its purpose and could no longer meet the increasing demands of the middle and lower social layers, the sanctuary of Delphi would not hesitate to take a clear opposing stance against it.

In Cyrene, during the reign of Battos III (ca. 550 B.C.), the Cyreneans, who had suffered major disasters during the rule of the previous king, ‘sent (an envoy) to Delphi to ask what regime they should adopt in order to live in a better way. Pythia commanded that they should invite a legislator from Mantineia in Arcadia’ (Arist. Politika 7, 1319b 18-22). The Oracle adopted a similar stance in regard to the late Peisistratid Tyranny: it supported the Alkcmaeonids -the Peisistratids’ primary opponents-, urged the Spartans to overthrow the Athenian tyranny and assisted Cleisthenes in achieving a smooth transition from tyranny to democracy.

The priests of Delphi were also involved in military conflicts: for example, during the Persian Wars their attitude, at least in the beginning, was markedly pro-Persian.

The heyday and prestige of the Panhellenic sanctuary

From the 8th until the early 5th century B.C., the sanctuary’s authority and influence reached its peak. The more people sought advice or information from it, the wider its range of expertise became on issues of geography, political balance and social frictions. Successful colonization broadened its influence and reputation and strengthened its leading position as a Panhellenic sanctuary. Furthermore, colonies as well as tyrants endowed the sanctuary with offerings brought by sacred envoys. Despite its conservative attitude on matters of religion and worship, the sanctuary almost invariably supported changes dictated by social needs.

The validity of Apollo’s oracles granted the legislation of the cities authority, as the role of Delphi was to guarantee social peace. The sanctuary did not invest the leaders with prestige by invoking divine command, it supported however their decisions by legitimizing them.

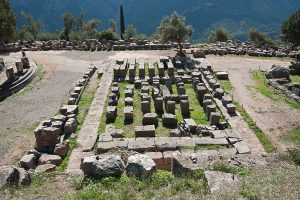

The earliest temple constructions

The Archaic period is considered to be the time in which the sacred site of Delphi began to take the form known today. The first poros stone temple was built in the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia, but was later abandoned due to damages caused by earthquakes. Similarly, the first historically documented Apollo’s temple, also made of poros stone, was built within Apollo’s sanctuary.

The first votive offerings-8th and 7th c. B.C.

In late 8th c. B.C., along with the offerings from all over Greece, imports from the East began to arrive in Delphi. These imported offerings were brought by Greek seafarers from Asia by way of the Greek trading posts of northern Syria (Al Mina, Tyre) and the islands of Crete, Cyprus and Rhodes. During the next century, the temple of Apollo became overwhelmed by a large number of luxurious metallic wares of innovative techniques and unusual decorative patterns. These artifacts originated either from the Near East which was home to the early Assyrian civilization, the Hittites and the state of Urartu (Armenia), or were imitations of eastern originals. Among those early offerings, the bronze tripods stand out: the Delphic tripod bears a particular symbolic value as it is associated with the oracular capacity of Apollo. It also played an important role in the very process of providing oracles, since Pythia could capture and transmit the divine knowledge only when sitting on the tripod that connected her with the chthonic powers.

The temples of the 6th c. B.C.

The first temple of Apollo was destroyed around the mid-6th c. B.C., most probably by an earthquake. Shortly thereafter, the prominent family of the Alcmaeonids fled from Athens to Delphi after their unsuccessful attempt to prevent Peisistratus from establishing tyrannis in their city. Apparently, the Alcmaeonids were seeking to resume their involvement in politics as well as making alliances. Therefore, they took the initiative to raise money from the Greek cities in order to build a new temple, which was completed in 510 B.C. Accordingly, in the sacred space of Athena Pronaia a new poros stone temple replaced the old one that had been demolished due to landslides.

The votive offerings of the 6th c. B.C.

During the 6th c. B.C. Delphi was flourishing. In 590 B.C. the dedication of the Krissa region to Apollo, as a result of the First Sacred War, vastly increased the Sanctuary’s wealth. This is the period when the Sanctuary’s political power grows, and rulers seize this opportunity to flaunt their wealth and power by dedicating expensive offerings and statues or even entire buildings. Thus, the large numbers of pilgrims had the opportunity to admire offerings of high artistic value.

The first treasuries were constructed during the 6th century along the Sacred Way leading up to the temple of Apollo. Treasuries were small buildings-dedications to the god, which housed precious ex-votos from the donor city. The first treasury on one side of the Halos, the small open-air square where outdoor rituals took place, was that of the Corinthians. It was dedicated by the tyrant of the city, Cypselus, inaugurating a tradition followed initially by other dynastic families and eventually by the cities as well. In ca. 560 B.C. Sicyon dedicated a monopteros (i.e. single-winged) building. The upper part was adorned with a doric frieze with metopes and triglyphs. The sculptural decoration of this treasury is an excellent example of the archaic art of Sicyon, renowned in antiquity, in which painting with precise contours and details of forms dominated over sculpture. Parts of this frieze were discovered later in the foundations of the Treasury of the Sicyonians. As far as the initial use of the monopteros is concerned, it has been suggested that it was used as a shelter for the chariot with which Cleisthenes won the chariot races of the Pythian Games of 582 B.C.

Next to the austere Doric buildings within the sanctuary of Delphi, the construction of which was ordered by the cities of mainland Greece, one finds the Treasury of the Siphnians which is dated to ca. 524 B.C. and, with its emphasis in architectural decoration represents the style of the eastern Greek islands and the Ionic order. Its remains allow for a rather detailed reconstruction. On the temple’s façade, instead of two columns in antae, the architrave was supported by two Caryatids, precursors to the Caryatids of the Erechtheion.

In the sacred space of Athena Pronaia, just before the dawn of the 5th c. B.C., the inhabitants of Massalia (Marseilles), a Phocaean colony, dedicated a very elegant treasury with exceptional sculptural decoration, probably in order to express their gratitude to the goddess for their victory over the Ligurians.

In terms of the movable artifacts, the city of Argos was the first to dedicate identical oversize statues, the pair of kouroi now exhibited in the Museum of Delphi. This is the oldest monumental ex voto at Delphi and one of the early examples of “great” Archaic sculpture, bearing the signature of the sculptor Polymedes of Argos. Initially, they were identified as Kleobis and Biton, two brothers from Argos, so strong and devout that they carried their priestess mother to the temple of Hera by pulling her cart the entire way. However, according to more recent research the two statues most probably represent the Dioscuri whose cult was widespread in the Peloponnese.

Around 560 B.C. Naxos, the rich island of the Cyclades, sent a magnificent offering to Apollo at Delphi. It is the statue of the mythical Sphinx whose colossal size, imposing form and position in the sanctuary (near Sibyl’s rock) highlights the political and artistic prevalence of Naxos during the Archaic period. The demonic creature with the face and enigmatic smile of a woman, the body of a lion and a bird’s plumage, was set upon the capital of an extremely tall ionic column, which is considered the oldest specimen of Ionic order in Delphi. Its colossal size and the height from which it commands the entire Delphic landscape must have been a source of awe for the pilgrims of the Archaic period.

From the same period come the renowned chryselephantine ex votos depicting Apollo, Artemis and Leto, now in the Museum of Delphi.

However, the most famous gifts which are described in detail by Herodotus (A, 51, 1-5) are the votive offerings of the Lydian King Croesus. These include, among others, two oversize craters, a golden and a silver one, four silver pithoi (jars), two perirrhanteria (sprinklers), also a golden and a silver one, and a golden statue of a female, apparently the woman who used to knead Croesus’ bread. Some of these offerings were destroyed during a fire; those which were preserved were kept in the treasuries of the Clazomenians and the Corinthians.

“When these offerings were ready, Croesus sent them to Delphi, with other gifts besides: namely, two very large bowls, one of gold and one of silver. The golden bowl stood to the right, the silver to the left of the temple entrance. [2] These too were removed about the time of the temple’s burning, and now the golden bowl, which weighs eight and a half talents and twelve minae, is in the treasury of the Clazomenians, and the silver bowl at the corner of the forecourt of the temple. This bowl holds six hundred nine-gallon measures: for the Delphians use it for a mixing-bowl at the feast of the Divine Appearance. [3] It is said by the Delphians to be the work of Theodorus of Samos, and I agree with them, for it seems to me to be of no common workmanship. Moreover, Croesus sent four silver casks, which stand in the treasury of the Corinthians, and dedicated two sprinkling-vessels, one of gold, one of silver. The golden vessel bears the inscription ‘Given by the Lacedaemonians,’ who claim it as their offering. But they are wrong, [4] for this, too, is Croesus’ gift. The inscription was made by a certain Delphian, whose name I know but do not mention, out of his desire to please the Lacedaemonians. The figure of a boy, through whose hand the water runs, is indeed a Lacedaemonian gift; but they did not give either of the sprinkling-vessels. [5] Along with these Croesus sent, besides many other offerings of no great distinction, certain round basins of silver, and a female figure five feet high, which the Delphians assert to be the statue of the woman who was Croesus’ baker. Moreover, he dedicated his own wife’s necklaces and girdles.”

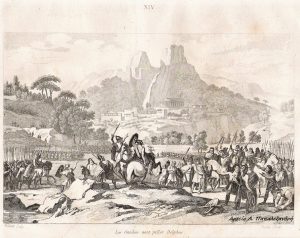

The dawn of the Classical period was marked by the Persian Wars, which didn’t leave Delphi unscathed, despite the pro-Persian attitude that the sanctuary seems to have held, with its ominous oracles to the Greek cities fighting against the Persians. According to Herodotus, in 480 B.C. the Persians, after their victory at Thermopylae, on their way towards southern Greece, sent a military unit to Delphi, in order to loot the sanctuary. It is reported that the inhabitants of the region sought refuge in the Corycean cave, which was difficult to locate. However, the Persian army never reached the sanctuary: they were driven away by two local heroes, namely Phylakos and Autonoos. Tradition has it, however, that rocks from two summits of Parnassus fell and blocked the way to the invading Persians, killing many of them.

Delphi remained autonomous until 448 B.C, when the Phocaeans, aided by the Athenians, attempted to annex the city to the Phocaean League. The Spartans’ reaction to this attempt resulted in the Second Sacred War. The Phocaeans, however, managed to gain control over Delphi, establishing a status quo which was maintained until 421 B.C. Later, in the course of the Peloponnesian War and during the (unfavourable for the Athenians) Peace of Nicias, Delphi regained its freedom. It maintained its independence until 356 B.C., when the Phocaeans captured the city in retaliation for a heavy fine that the Amphictyonic Convention had imposed on them. This episode triggered the Third Sacred War and instigated the involvement of Philip II of Macedonia in Central Greece politics. Finally, the Fourth Sacred War, of relatively short duration, broke out in 339 B.C., instigated by the actions of the Locrians of Amphissa; the war eventually led up in the Battle of Chaeroneia (338 B.C.) and the final subjugation of the rest of Greece to Philip and the Macedonians.

The evolution of the sanctuary in the classical period

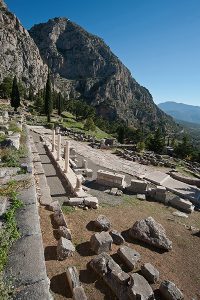

Important and famous buildings were erected in Delphi during the classical period. Along the Sacred Way several buildings were placed, such as the Treasury of the Athenians, the Portico of the Athenians, the Treasury of the Megarians, the Treasury of the Thebans etc. The temple of Apollo, situated at the end of the Sacred Way, was rebuilt in ca.330 B.C. (late classical period), whereas the altar of the temple (altar of the Chians), which had been built around 475 B.C., was restored in order to match the temple architecturally. The area around the temple was decorated by artistic masterpieces, such as the Monument of Daochos, situated in front or (most probably) within the Treasury of the Thessalians. Within the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia the Tholos and the Doric Treasury were built and, slightly later, the limestone temple. Towards the end of the classical period the first buildings of public and athletic character were constructed, such as the Gymnasium, between the sanctuary of Athena and the Castalia Spring, and the Stadium, above the temple of Apollo.

Finally, during the classical period ex-votos of high artistic value were put up at Delphi. Some of the preserved offerings allow us a glimpse into the wealth that had been accumulated in the city and the sanctuary after the Persian Wars. The famous Charioteer, one of the masterpieces of the so-called “severe style” which marks the transition from the archaic to the classical period, as well as smaller bronze offerings, such as the incense burner in the form of peplophoros supporting a cauldron, the Flute Player and the pair of athletes, which have been found within the dump pit of the Sacred Way, are but a few specimens of early classical art. Unfortunately, many offerings were destroyed during the Third Sacred War, whereas others were transported to Rome after the Roman conquest. It seems, however, that in the 2nd century A.D. there were still several statues extant in situ, according to the testimonies of Pausanias and Plutarch. The latter describes in detail, for example, the sculpted group consisting of 37 statues that the Lacedaemonians had dedicated after the battle at Aegos Potamoi (405 B.C.), their ultimate victory during the Peloponnesian War. Apparently, the Lacedaemonians followed a practice established by the Athenians in 460 B.C., when they assigned to Pheidias the task to create a sculpted group of 13 statues using metal from the booty of the Persian Wars. Great sculptors, such as Ageladas from Argos and Onatas from Aegina were among the artists who adorned with their works the sacred sanctuary of Apollo.

At the end of the classical period, a time when the army of Alexander the Great was already marching in the East, another masterpiece marks the transition towards the Hellenistic art: the “Three Dancers”, the sculpted complex of three maidens which seems to stem from a 10-meter tall column wrapped in acanthus leaves, supporting an elaborate tripod within which the “omphalus” apparently stood The column was set up on the occasion of the Pythaid of 330-325 B.C. Recent interpretation has shown that the dance-like position of the hands was actually a way to support the tripod; the three female figures were probably depicting the three daughters of the mythical Athenian king Cecrops

After the turbulent 4th century, Delphi entered a new phase of prosperity and power during the Hellenistic period. The panhellenic sanctuary received its share of the booty gathered during Alexander’s campaigns in the East. The rivalries among his Successors and, later on, the Hellenistic kingdoms and confederacies, were often reflected in their effort to surpass one another in lavish and prestigious votive offerings.

The threat of the Galatians and the rise of the Aetolian Confederacy

The third decade of the 3rd century B.C. found the Hellenistic states exhausted by constant fighting; great dangers loomed over Greece. The defeat and death of Lysimachos at the battle of Kouropedion in 281 B.C. and the weakening of his state in Thrace mobilized the Celtic tribes (Galatians) that dwelled in Pannonia to descend towards Greece, possibly driven by famine.

When they reached Northern Greece, their military, a total of about 85,000 men, was divided in three groups. The main group, under Brennus and Acichorius, headed towards central Greece, whereas the other two towards Western Macedonia and towards Eastern Macedonia and Thrace respectively. The initial raids ended once the need of the Galatians for booty was satisfied yet Brennus and Acichorius organised another campaign in 279 B.C. The Greeks joined forces and tried to stop them at Thermopylae. Brennus sent part of his military force to the east, towards Aetolia, as a decoy, in order to force the Aetolians who defended Thermopylae to abandon their positions. The Galatians destroyed Kallion, on the border between Eurytania and Aetolia, committing horrible atrocities, but the resistance of the entire Aetolian population at the site Kokkalia, where even the elderly and the women and children fought, gave a decisive blow to the Galatian threat. The Galatian army was defeated and the planned looting of Delphi never took place. On the contrary, the Aetolian League strengthened its position in mainland Greece and dominated Delphi for about a century. The Aetolians set up a honorary stele on a base which presumably depicts pieces of armoury of the Galatians; they also erected the so-called “Portico of the Aetolians” or Western Portico, one of the largest buildings close to the sanctuary of Apollo. As a token of gratitude, they were accorded the right to participate at the amphictyonic convention. Honorary games were organised too – the Amphictyonic Soteria, which in 246 B.C were renamed “Aetolian Soteria” and later evolved into Pan-Hellenic Games which took place every five years.

The Attalids and Delphi

The Hellenistic kingdom of the Attalids in Pergamon also acquired prestige through its fight against the Galatians who reached central Asia Minor after their defeat in Greece. At about 241 B.C. Attalus I inaugurated the construction of a monumental portico to the east of the sanctuary of Apollo. Part of the sacred precinct had to be demolished to make room for this construction. The Attalids were also given the right to be the only ones who could erect votive offerings within this portico. Later, in ca. 160 B.C., Eumenes II provided the theatre of Delphi with stone benches.

The War of the Allies

The strengthening of the Aetolian League alarmed most of the other Hellenistic states, except for the Attalids, who considered the Aetolians their allies in their common goal of controlling the Galatians. Philip V of Macedonia, eager to put an end to Aetolian supremacy over Central Greece, managed to bring together several Greek powers in the so-called War of the Allies. Although the war did not terminate the Aetolian presence in Delphi, it did weaken their control over the sanctuary and the oracle. Thus, when Sicyon, a member of the Achaean League which was rival to the Aetolian League, asked in 213 B.C. the oracle for advice on how to bury its king, Aratus, the answer was that Aratus should be proclaimed a hero.

Towards the end of the 3rd century B.C., however, a new power, Rome, emerged and became actively involved in the political life of the Greeks. The sanctuary of Delphi foresaw the role Rome was to play and made sure to offer its support. Delphi’s pro-Roman position was going to be long-lasting.

The Hellenistic ex-votos

In terms of art, the beginning of the 3rd century was characterized by a turn towards realism. The first large Hellenistic ex votos is a sculpted composition to which seem to belong the statue of Dionysus and that of a bearded elderly man (known also as the “Philosopher”), as well as the figures of a woman and a girl. If these statues did actually form a group, they must have been dedicated by a priest at Delphi around 270 B.C. In the course of the 3rd century the robust style of the classical period is succeeded by forms of little children, such as the boy holding a goose with both hands (a type which has been amply reproduced in the Hellenistic and Roman period), or the arktos (bear) type of little girl, similar to the votive offerings to Artemis at Brauron, and the sleeping Cupid.

The ongoing wars which exhausted the Hellenistic kingdoms financially had also repercussions on the Sanctuary of Delphi, as the number of its ex-votos diminished and its financial power waned. The last ex-voto which was set up at the site to commemorate a military victory was the pillar which supported the statue of Aemilius Paulus on horseback, the Roman general who won the Battle of Pydna in 168 B.C. However, in 86 B.C, another general, Sulla, would plunder many of the treasures of Delphi under the pretext of “loan”. Three years later raids by Thracian tribes would bring yet more destruction. Strabo, who visited the area in the 1st c. B.C., renders in his writings an image of abandonment.

After the end of the Republic, however, the Roman emperors undertook the task of maintaining and preserving Delphi. Some of them made sure to renovate buildings, donate new votive offerings and continue the Pythian Games. Not everyone though: Nero, who went to Delphi and competed at the Games (and, obviously, won), took with him approximately 500 bronze statues from the sacred precincts. On the contrary, Trajan tried to restore the glory of the sanctuary. At the end of his reign, Plutarch took on the priesthood at the sanctuary and remained there for thirty years (95-125 AD). The work of Plutarch is a source of abundant information on the rituals, the monuments as well as the visitors of the sacred land.

Yet, the emperor whose name became most closely linked with Delphi was Hadrian, who deeply admired Greece, its art and its philosophy. A great number of statue bases bear his name, but none of his statues has been preserved. Instead, a statue of his protégé, the young Antinous from Bithynia, was preserved. Inconsolable after the loss of his companion’s, Hadrian gave orders to place statues of Antinous in almost every spot in the empire. The statue discovered in Delphi, however, is probably the most beautiful of the surviving specimens, an idealized figure, made to last for eternity.

Around 170 A.D. Delphi welcomed one final great benefaction: Herod Atticus is reported to have undertaken the revetment of the stadium with marble benches, as he had done with the stadium in Athens. From then on, the Oracle and the site began to decline. In about the same period, Pausanias visited the site and gave detailed descriptions of the sanctuary which was rapidly degenerating. Without his texts many of the monuments would have been nowadays unknown or unidentified.

Ex-votos of the Roman period

Unfortunately, during the “Great Excavation” the Roman ex-votos were treated as “less significant”, a view that has changed ever since. The stele of Aemilius Paulus is a very important historical token since it portrays on its frieze the Battle of Pydna. The bust of the “melancholic Roman”, none other than Titus Quintus Flamininus (229-174 B.C.), the protagonist of the Second Macedonian War, is consistent with Plutarch’s description in his homonymous “Life”.

Extremely interesting is the renowned “Sarcophagus of Meleagros” that was found at the beginning of the 19th c. in situ in the western necropolis, and was later transferred to the Museum of Delphi. It is dated to the 2nd c. A.D. and it is adorned with a relief decoration depicting the myth of the Caledonian Boar and the conflict between the hunters who were chasing it. The lid of the sarcophagus is formed like a bed on which a female figure is lying, most probably the deceased woman.

The Oracle of Delphi had started vacillating before its actual final abolition at the end of the 4th century A.D. Already in the course of the 3rd century the Mystery Cults of the East had prevailed in the subconscious of the pious flock, who asked for a revelatory truth rather than mere oracles. The anti-pagan legislation of Constantine the Great and his successors, particularly of Constantius, was a severe blow to the ancient sanctuaries. The removal of precious ex-votos and its remaining property deprived Delphi of the necessary funds for its existence. The pagan emperor Julian tried in vain to reverse the religious climate. The answer that his envoy, the famous doctor Oreibasios, received when he visited Delphi in order to ask for an oracle for the future of the pagan world, left no hope:

Εἴπατε τῷ βασιλεῖ, χαμαὶ πέσε δαίδαλος αὐλά,

οὐκέτι Φοῖβος ἔχει καλύβην, οὐ μάντιδα δάφνην,

οὐ παγὰν λαλέουσαν, ἀπέσβετο καὶ λάλον ὕδωρ.

[Tell the king that the flute has fallen on the ground. Phoebus doesn’t have a home any more, nor an oracular laurel, nor a talking fountain, because the eloquent water has dried out]

This is considered to be the last prediction ever pronounced by the oracle. In 394 Theodosius I issued a decree which banned the oracles in the entire Roman Empire. However, the archaeological data from the Late Roman period, particularly the excavation reports of the 1990s, prove that life in Delphi did not stop in the 4th century. On the contrary, the city seems to have continued to exist and to offer its inhabitants high living standards for three more centuries. In the course of the Great Excavation there were discovered capitals, parapets and slabs from an early Christian basilica (5th century), when Delphi was a bishopric. Other important Late Roman buildings are the Eastern Baths, the peristyle house, the Roman Agora, the large cistern, the mansion in the western portico as well as the tombs outside the city, and the pottery kilns at the Gymnasium.

Among these monuments, the Southeastern Mansion, which has been excavated to the southeast of the precinct of the sanctuary of Apollo constitutes an important token of the prosperity and fine aesthetics of its inhabitants. It is a building with a 65-meters long façade, built on four different levels. It has private baths as well as four triclinia, of which three end up in niches. In its storage spaces large jars were discovered; in the rest of the rooms were found luxurious items and vessels. Among them stands out a small leopard made of mother-of-pearl, apparently of oriental provenance, possibly from Sassanian Persia; it was used as a decorative element for a small scepter or for a seatback. It seems that the building was used as a private house from the beginning of the 5th century until about 580 A.D. In about 590 it was transformed into an industrial centre where potters had settled. It is in this period that an abrupt change took place in the life of the city of Delphi, causing a demographical decline. The settlement shrank in size, the imports of luxurious items ceased and the local pottery production increased. Whereas the imported pottery items consist mainly of tableware, notably made of fine terra sigillata, the local products – amphoras, jugs, cooking pots etc – are coarser, made of red clay with addition of mica.

It is interesting to follow the changes of use of the area after the oracle and the sanctuary ceased functioning. The Sacred Way remained the main street of the settlement and was in fact paved anew using ancient building material. However, its character had now become primarily industrial and commercial. In the Roman Agora important workshops were excavated with pottery finds dating to the 4th century, of which one was perhaps used for making glass. Scattered architectural members indicate that maybe on that spot was built the only intra muros early Christian basilica. The western part of the site was the residential area, with large houses, many of which were provided with triclinia. Two large cisterns supplied water to the city as well as to the large bath complex built against the support wall of the sanctuary. As mentioned before, the city of Delphi was abandoned after the first decades of the 7th century, probably around 620 A.D. or slightly later.

Τhe area of the archaeological site of Delphi did not recover as a settlement until the early Ottoman period. When the Byzantine Empire collapsed after the Fourth Crusade, the region was occupied in 1205 by Boniface, Marquis of Montferrat, king of Thessaloniki. Following the western feudal system, the new monarchs distributed the land to title holders, officers of the military and their attendants. Amphissa and its surrounding area, for instance, was renamed La Sole (Salona) and was given to the D’ Autremencourt family (often paraphrased as Stromoncourt).

The first count of Salona was Thomas who originated from Picardy in France. Through a series of military operations he expanded his dominance to almost all of Phocis. However, in his attempt to conquer Galaxidi he faced resistance by the Despot of Epirus Michael I Komninos Doukas and was killed in a battle in 1212. The Byzantines managed to prevail for a short period, however the son of D’Autremencourt, Thomas II, regained control of the area which remained under Frankish rule until 1318. In that year the Catalan Company, consisting mainly of mercenaries, took hold of the Duchy of Athens to which the D’Autremencourt family was subject. The Catalans remained masters of Thessaly, Boeotia, Attica and Phocis until approximately 1390, when their possessions were taken over by the Navarrese Company. The next two decades were especially turbulent, with continuous disputes between the Latin conquerors and the Byzantine Despots of Morea. Tired from the military turmoil but also fed up with the tyrannical Elena Asanina Katakouzene, widow of the last master of Salona, Ludwig Frederic of Aragon, the inhabitants of Amphissa opened the gates of the city in 1394 to the army of Beyazid I, who was moving southwards through Central Greece, invited by the Byzantines. In 1402 the region was conquered by the Despots of Morea and two years later Thomas Palaeologos sold it to the Knights of St. John. Nevertheless, the Ottomans returned once again and conquered it permanently in 1410.

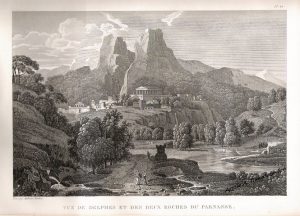

Delphi shared the history of Phocis, with successive changes of suzerains in the course of the Frankish period down to 1410, when the Ottomans gained a firm hold over the region. The area itself remained almost uninhabited for centuries, whereas it seems that one of the first buildings of the early modern era was the monastery of Panayia (the Mother of God) built over the ancient Gymnasium. A settlement that began to form, gradually evolved into the village of Kastri.

Cyriacus of Ancona and his narration

The first western “traveler” who described the visible archaeological remains in Delphi and offered a rare view of the area in a rather obscure period was Cyriacus of Ancona (his real name was Ciriaco de Pizzicoli). He was a brilliant personality, a genuine representative of Renaissance humanism. He started his career as a merchant, yet the antiquities he encountered during his travels moved him deeply and motivated him to learn ancient Greek and Latin at the relatively advanced age of 30. He then pursued a series of travels aiming at archaeological investigation and documentation, along with undertaking various diplomatic missions, particularly in the Ottoman court. Cyriacus visited Delphi in March 1436, in the course of a journey to Greece and the eastern Mediterranean, and spent six days there, recording the archaeological remains with Pausanias’ text as his guidebook. Thanks to him we have learned about the condition of the theatre and the stadium as well as many visible statues. He also contributed to the field of epigraphy by recording a considerable number of inscriptions. His identifications, however, were not always correct: for example the round building that he described as the temple of Apollo was none other than the two semi-circles of the base of the Argives’ ex-voto.

Our information for the next two centuries of Ottoman rule is relatively sparse and rather confused. Under the name Kastri, Delphi was subjected to the kaza of Salona (Amphissa). We know that the destructive earthquake of 1580, which affected the entire Amphissa region, caused severe damage to the antiquities.

The foreign travelers

Information on Ottoman Delphi became more abundant as the travelers who visited it increased. In Ottoman times as in antiquity, one of the main roads which connected Eastern and Western Greece passed through the region of Delphi. Many travelers disembarked at Itea or Naupaktos and then took the long way to Delphi, aided by beasts of burden such as donkeys, mules and horses.

From the mid-17th century onwards, such visits became more frequent, as the idea of traveling and collecting antiquities became fashionable throughout Europe. Two of the earliest (recorded) visitors of Delphi were George Wheler and Jacob Spon, who passed by in January 1676. The first building to have attracted their attention (as well as that of many other travelers in the years to follow), was the monastery of Panayia built in the region of “Marmaria”, right on top of the ancient Gymnasium. It was an annex of the Monastery of Jerusalem situated in Davleia in Boeotia and it stood there until its demolition during the “Great Excavation” in the 1890s. Many travelers sojourned in this monastery; most of them mention the excellent wine offered by the – otherwise frugal – monks.

In 1766 a group of travelers passed from Delphi: Richard Chandler, a professor in Oxford specialized in epigraphy, Nicholas Revett, an architect and designer, and William Pars, a painter. Their expedition had been funded by the renowned Society of the Dilettanti, which systematically promoted the interest in Greco-Roman antiquities in Great Britain. The results of their research were published in 1769 under the title “Ionian Antiquities”, followed by a compendium of inscriptions as well as two travelling accounts, one about Asia Minor (1774) and another about Greece (1775). Apart from the antiquities that they recorded, they also produced some vivid descriptions of daily life in Kastri, particularly the visit of a band of Turco-Albanians, whose duty was to guard the mountain passes. These men appalled the British with their “barbarian” and “crude” behavior.

In 1805 Edward Dodwell visited Delphi, accompanied by the painter Simone Pomardi. His descriptions are simple but precise, and so are the fine engravings by Pomardi, which illustrated his book, published in 1821. Apart from the antiquities, he also depicts scenes of daily life, such as a memorable dinner at Chrisso, or the hospitality offered by the priest of Kastri in a plain, single-room house with no ventilation for the smoke coming out of the hearth. The family lived together, without any sense of privacy.

A well-known travelling destination such as Delphi could not have escaped the philhellene Lord Byron, who visited in 1809. Byron was accompanied by his friend John Cam Hobhouse. The poet was inspired by this visit to write – among other things – the following verses:

Yet there I’ve wandered by the vaulted rill;

Yes! Sighed o’er Delphi’s long deserted shrine,

where, save that feeble fountain, all is still.

At the same time he couldn’t help but notice the incised signatures of other visitors on the ancient columns, which were re-used at the monastery of Panayia; among these was the signature of the Count of Aberdeen, whom Byron accused, as he did with Lord Elgin, for the mutilation and steeling of antiquities. His horror at the abominable actions of his compatriots, however, did not prevent him from leaving his own signature on the marble of the same column, nowadays standing restored in the Gymnasium of Delphi.

The first decades of the Greek state

After the liberation of Greece and the foundation of the Modern Greek State, care for antiquities was immediately taken throughout the country. Several sculptures found in situ in Delphi were initially transported to Aegina, to the first museum founded by governor Capodistria. However, there was a persistent demand for the foundation of a museum in the region of Delphi itself. An excavation of the entire region had been planned since the 1860s, but the limited financial resources of the Greek state rendered this perspective almost impossible. Meanwhile, foreign travelers continued to visit Delphi. One of them was the French poet and author Gustave Flaubert, who visited the site in 1851. Τhe increasing numbers of visitors and amateur antiquaries possibly contributed to the final achievement of a deal between the French and Greek state for the expropriation of the village Kastri, the relocation of the inhabitants and their houses, and the realisation of the largest, until then, excavation on Greek soil.

MUSEUM OF DELPHI