History of Delphi

Delphi were not chosen randomly in antiquity for the construction of the temple and the oracle of Apollo, neither for their attribute as “navel of the earth”. The location has an amazing dynamic cretated by the strong energy flow, the naturally fortified spot with a unique view to the gulf og Itea along with the rich vegetation, sources which sprang from the rocks and a strategic location on the mountainous routes which connected eastern and western Mainland Greece.

It is possible that in this region existed a sanctuary dedicated to Gaea (Earth), due to the gaps on the ground, from where gas were released; when one came in contact with this gas one fell in trance. According to mythology, this ancient oracle was guarded by an

enormous serpent called Python. The god Apollo managed to kill the chthonic beast and then the oracle passed in his own jurisdiction. However, it is possible that this “prehistory” of the area is a later mythological

construction.

In the Iliad the oracle is already mentioned as rich ans powerful. It seems that it reached its peak at the end of the archaic and the beginning of the classical period, when the temple of Apollo was erected along with the oracle and the oracle archive it housed. In

the same period were built also most of the treasuries of the Greek cities, where ex votos were kept, precious either as artefacts or for their significance for the collective memory of the citizens (booty of battles etc). The oracle was related to two important facets of Greek history: the colonization and the Amphictyony. According to tradition, the Greek cities asked the oracle of Delphi to suggest a location for the establishment of their colonies. On the other hand, after the First Sacred War, Delphi became the sea of the Amphictyony, i.e. the confederation of Central Greece, a fact which sealed their later history. Around that time were permanently established the Pythian

Games, sacred athletic contests in honour of Pythian Apollo, which acquired a panhellenic status as well as a prestige similar to that of the Olympic games. The evolution of Delphi within the ancient world, therefore, is not accidental and thus the declaration of the present archaeological site as a World Heritage Monument was not random. The enhancement of the uniform architectural complex through systematic excavations at the end of the 19th century and during the first half of the 20th century, the danger it faces due to the steep inclination of the ground and the constant slandslides and particularly the importance of Delphi as an oracle, a centre of political and cultural evolution, as a panhellenic sanctuary and a place where panhellenic games were organized made the preservation of its history and of its archaeological remains as well as of the values which emerged through it an absolute necessity.

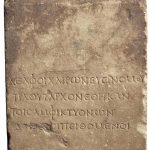

The most important of these values are summarized in the so-called Delphic maxims, which were inscribed in the

vestibule of the temple, which developed into symbols of the Greek thought, reaching, in the Hellenistic period particularly, the extremities of the Greek world.

See also: The written sources and the variations relating to the foundation myth of the sanctuary of Delphi and The historical evolution of the Oracle

Apollo was the god who symbolized light and regeneration, the protector of the arts and the highest manifestations of the spirit.

The qualities and characteristics of Apollo

As in most other ancient religions, there are many mythological versions regarding the birth and deeds of the god. Apollo was born on the 7th day of the month Vyssios, the first month of spring. When he was still an infant, he had to kill with his bow the Python, the dragon or snake which symbolized the powers of the underworld. According to another version, he killed the dragon at Tempi or in Crete when he was older and then he exiled himself to the land of the Hyperboreans, in order to be cleansed from the murder. In Attica Apollo’s return from the Hyperboreans and the regeneration which followed it were celebrated on the 6th and 7th days of the month Thargelion; on the first day there were lamentations whereas on the second joyous paeans were sung. The relation of Apollo with the underworld and his dominant position in the eternal game of death and rebirth is symbolized by the conviction that within the tripod of Delphi had been buried the remains of the Python or, according to the Orphic philosophers, the body of Dionysus who had been dismembered by the Titans.

The most important element of the cult of Apollo, ensuing exactly from his relation with the underworld and from his dominance over it, is the art of pronouncing oracles. According to the “theology” which developed in the Delphic cult, Apollo was incarnated through Pythia and gave the oracles himself. In extension of this power he had, Apollo became the regulator of the political and social life. The fact that the first codification of legislation was taking place on the walls of Apollo’s temples is not irrelevant to that.

Another well-known attribute of Apollo was music. Both in mythology and in art Apollo plays either the guitar or the lyre. His depiction in this form is relatively early, as proved by a Boeotian statuette from Thespies. Another myth, related to music, particularly popular among artists of later periods, was that of the contest against the satyr Marsyas, who dared challenge the god by saying that the flute was superior to the lyre. Apollo was enraged as he almost lost at the contest and he punished Marsyas very harshly: he tied him to a tree and skinned him alive. In the myth of Marsyas, however, is evident one element which is essential to the cult of the god as well as to the philosophical thought which followed, namely the differentiation between the apollinian element, symbolizing light, clarity of spirit and high ideals, and of the dionysiac element, symbolizing the world of passions and ecstasy. This distinction will be adopted by later European thought, culminating in the philosophy of Nietzche.

The qualities and characteristics of Apollo

Archaeological data point to the establishment of the cult of Apollo in ca. 1000-800 B.C. The function of the site as a cult centre is archaeologically attested since 860 B.C., and it evolved throughout the 8th century B.C. Other important sanctuaries of Apollo were situated on Delos island, where the god and his sibling, Artemis, were born, in Phigaleia (temple of Apollo Epicurean), at Didyma (a city-temple close to Miletos), in Claros and in Colophon; other sanctuaries, not as well-known and yet very early (9th century), are found at Yria in Naxos and at Epidaurus. The cult of Apollo was also transferred to Rome at an early date: starting out from the sanctuary and oracle at Cymae in Asia Minor, the cult was introduced to Rome in 431 B.C., in order to protect the Romans from an epidemic. Apollo was probably the first Greek deity to have been incorporated in the Roman pantheon.

Archaeological data point to the establishment of the cult of Apollo in ca. 1000-800 B.C. The function of the site as a cult centre is archaeologically attested since 860 B.C., and it evolved throughout the 8th century B.C. Other important sanctuaries of Apollo were situated on Delos island, where the god and his sibling, Artemis, were born, in Phigaleia (temple of Apollo Epicurean), at Didyma (a city-temple close to Miletos), in Claros and in Colophon; other sanctuaries, not as well-known and yet very early (9th century), are found at Yria in Naxos and at Epidaurus. The cult of Apollo was also transferred to Rome at an early date: starting out from the sanctuary and oracle at Cymae in Asia Minor, the cult was introduced to Rome in 431 B.C., in order to protect the Romans from an epidemic. Apollo was probably the first Greek deity to have been incorporated in the Roman pantheon.

Priests, rituals and celebrations

In each of the aforementioned areas the rituals and the form of the cult, of course, differed. Yet, the god’s cult in Delphi itself is probably more interesting and important. From archaeological and epigraphic testimonies it is deduced that there were two priests (maybe three in the 1st century B.C.), appointed for life. Delphic chronology was organised on the basis of the succession of the priests. Another life-long office was that of the neokoros, whose tasks are not particularly clear, yet he might have been a kind of superintendent of the temple. We know, however, that he was present in all acts of liberation of slaves, as attested on the manumission inscriptions. Plutarch, himself a priest at Delphi for a considerable part of his life, speaks also of the Hosioi (the Sacred Ones), a council consisting of five men, head of which was the “presvys of the hosioi” (elderly). These men were present during several ceremonies, yet they must have played a role also in the administration of the assets and property of the sanctuary. Administrative roles were held also by the “protectors” and the “epimeletes” (curators), who undertook several tasks of a practical character during various celebrations.

In each of the aforementioned areas the rituals and the form of the cult, of course, differed. Yet, the god’s cult in Delphi itself is probably more interesting and important. From archaeological and epigraphic testimonies it is deduced that there were two priests (maybe three in the 1st century B.C.), appointed for life. Delphic chronology was organised on the basis of the succession of the priests. Another life-long office was that of the neokoros, whose tasks are not particularly clear, yet he might have been a kind of superintendent of the temple. We know, however, that he was present in all acts of liberation of slaves, as attested on the manumission inscriptions. Plutarch, himself a priest at Delphi for a considerable part of his life, speaks also of the Hosioi (the Sacred Ones), a council consisting of five men, head of which was the “presvys of the hosioi” (elderly). These men were present during several ceremonies, yet they must have played a role also in the administration of the assets and property of the sanctuary. Administrative roles were held also by the “protectors” and the “epimeletes” (curators), who undertook several tasks of a practical character during various celebrations.

The establishment of the Sanctuary at Delphi

The myth goes that Zeus decided to establish an oracle at the center of the world. In order to find the suitable location, he let loose two eagles, the first flying towards the East and the second towards the West. The two eagles met above Delphi indicating that this was the center of the world, the omphalos or navel of the earth (Gaia).

Geographically, Delphi is situated at the heart of central Greece. The valley of the small river Pleistos is the natural passage from eastern to western Greece. At the same time, topographical studies showed that the road starting from Kirrha, the harbour-city of the Pleistos Valley, and passing through Gravia and the area of Mt. Oeti by way of Amphissa, connected the gulf of Krissa with the Malian gulf and Thessaly since the Mycenaean period (1500-1100 BC).

Delphi was built on the remains of a Mycenaean settlement. Tradition has it that initially there was a temple dedicated to the female goddess of the Earth (Gaia), guarded by the fierce dragon Python. Apollo killed Python and founded his own sanctuary there, manning it with Cretan priests, who arrived in Kirrha, the seaport of Delphi, having followed the god who had transformed himself into a dolphin. This myth was kept alive via ritual reenactments at Delphi, in festivals such as Septeria, Delphinia, Thargelia, Theophania, and the Pythian Games, which were held to commemorate the victory of the god over Python and included musical and gymnastic competitions.

Archaeological excavations have brought to light female figurines and a ritual vessel. This evidence was seen as archaeological proof of the later literary tradition regarding the existence of a “primitive” Oracle with goddess Gaia as its first priestess. This tradition was adopted by the Delphic priesthood and propagated by the poets of the 5th century B.C. Current scholarship questions the historical validity of the myth, considering that dating the Oracle’s establishment in prehistoric times is merely in accordance with the general theogonic conception, according to which the Greek pantheon evolved from the chthonic deities into the heavenly gods.

The Delphic Amphictyony

Amphictyony (or Amphictiony) was the name of the standing convention of the “amphictyons”, i.e. those who dwelled around a major sanctuary. The formation of amphictionies was initially dictated by the need to make decisions regarding the sanctuaries. Gradually, however, as the meetings of the representatives of the city-states took place at regular intervals, they became opportune for exchanging views on other issues as well, of interest to all parties, or for settling disputes. The establishment of amphictionies was a process which evolved towards the mid-8th century. Known amphictionies of the ancient world were that of Boeotian Oghestus, organised around the temple of Poseidon, that of Delos around the temple of Apollo, the one at Argos around the temple of Pythaeos Apollo, the one of Kalavria (nowadays the islet Poros in the Saronic Gulf) and the one of Trifylia, both centered around the respective temples of Poseidon, as well as the amphictiony of the six Doric cities of Asia Minor. Although several such conventions had been founded, the term “Amphictyony” soon came to denote the Delphic Amphictyony, as Amphictyony par exellence.

The seat of the Amphictyony was initially the sanctuary of Demeter “Amphictyonis” close to Anthele at Thermopylae (which was called “Pylae”, i.e. “Gates” , at the time). From the 7th century B.C. and after the First Sacred War the seat was transferred to the temple of Apollo at Delphi; the members of the Amphictyony declared the city independent, so that none of the member states would have the supremacy. The Amphictyony would convene twice a year, in the spring (Sping Pylaea) at Delphi and in autumn (Autumn Pylaea) at Thermopylae; that’s why the Amphictyony bore also the attribute “Pylaeo-Delphian”.

Ancient sources (such as Aeschines, “On the False Embassy”, 116) mention the following twelve tribes as members of the Amphictyony: the Aenians, the Achaean Phtiotae, the Boeotians, the Dolopes, the Dorians (initially only the inhabitants of Doris in Mainland Greece, later on also the Dorians of the Peloponnese and particularly the Spartans), the Thessalians, the Ionians (from Athens and Euboea), the Locrians, the Malieans, the Magnites, the Perrhaevoi and the Phocians.

The Amphictyony was administrated by the Amphictyonic Convention and the Amphictyonic Ecclesia. Two representatives from each of the 12 tribes, i.e 24 permanent members elected by lot, plus the Pylagorans (one from each city), one Secretary and a Hierophant composed the Convention.

The Hieromnemons formed the governing council and were responsible for all issues concerning the sanctuary.

The Pylagorans or Agoratroi were the representatives of the amphictyonic cities, who were elected each year and were charged with the protection of the interests of their cities in the Amphictyony.

Finally, the Amphictyonic Ecclesia consisted of the Hieromnemons, the Pylagorans and those who were at the sanctuary at the time of its convention. The Ecclesia was charged only with the responsibility of issuing decrees and did not possess much power.

Most of the times the Convention ran smoothly, although not always entirely free of antagonism for supremacy: in the 6th century this was in the hands of the Thessalians, in the 5th and 4th centuries the Convention was controlled by the Spartans and after 371 B.C. by the Boeotians. After 346 B.C. it passed on to Philip, in the 3rd century B.C. to the Aetolians and from 168 B.C. onwards to the Romans. In the Roman era the panhellenic radiance of the Amphictyony diminished and later on the Emperor Hadrian founded a new institution for the unity of the Greeks, namely the Panhellenion.

The shifts of supremacy among the tribes did not occur without turbulence. The so-called “Sacred Wars” are testimonies to this.

The decline of Delphic Amphictyony

In 336 B.C., after the assassination of Philip II, his son Alexander gained the acknowledgment of his supremacy over the Greeks by the Amphictyonic Convention at Thermopylae. It had already become evident that the Amphictyony had chosen security over autonomy.

In 279 B.C., after their struggle against the Galatians, the Phocians re-joined the Amphictyony, whereas, for the same reason, the Aetolians also acquired the right to one vote. In 171 B.C. the Amphictyony had 17 members, of which only the most powerful ones had two votes. It is evident that as the political importance of the city-state receded in favour of other political entities, from the Hellenistic period onwards, the importance of the Amphictyony shrank as well. The fact that the violent intervention of the Aetolians did not cause another sacred war (as it would have done a couple of centuries earlier) seems to support this view Yet the institution continued to exist throughout the Roman period, but its role was now confined to the protection of the sanctuary. Augustus merged the Aenians, the Malieans, the Magnetes and the Phocians with the Thessalians and he also gave the vote of the Dolopes, who had meanwhile disappeared as a tribe, to the city that he built in Epirus in 28 B.C.: Nikopolis.

The Panhellenion

In 131-132 A.D., Emperor Hadrian created a new confederacy of the Greek cities of the entire Roman Empire, called “Panhellenion”. Its official inauguration took place during the opening ceremony for the temple of Olympian Zeus at Athens. Cities from at least five Roman Privinces, namely Achaia, Macedonia, Thrace, Asia and Crete-Cyrenaica, had the right to participate at the Panhellenion provided they could prove their Greek origin. Each city was represented by one Panhellene, who served for one year, whereas head of the institution was the archon of the Panhellenion, appointed for 4 years. The seat of the Panhellenion was Athens, which thus emerged as one of the most prominent religious centres of the time, a fact which helped the city maintain its cosmopolitan character. The Pantheon, a Roman basilica with a capacity of 6.000-10.000 people to the east of the Roman Agora in Athens is identified by several scholars as the meeting point of the Panhellenes, whereas Hadrian was possibly worshiped at the Olympieion along with Zeus Panhellenios and Hera Panhellenia.

The foundation of the Panhellenion, one of the most important cultural and political institutions of the Antonineian period, constitutes one of the most vital interventions of a Roman emperor in the cultural life of the Greek world and shows the desire of Hadrian to be in contact with all the Greek cities. However, its political importance has been contested. The Panhellenion never became an institution with deep roots, and after Hadrian’s death it simply faded away.

Introduction

The Pythian Games were the second most important Panhellenic games in Greece after the Olympic ones. According to tradition, after Apollo murdered Python, he established musical competitions to commemorate that event.

The beginning of the Games dates to the early 6th century B.C, although some celebrations must have existed before as well. Initially, the games took place every 9 years – the same amount of time during which Apollo was absent, in order to cleanse himself from the murder of the beast. Paeans were sung to honor the god, accompanied by the sounds of the guitar. The games took place close to Krissa and the winners received a monetary prize.

After the First Sacred War, the games were reorganized following the model of the Olympian Games and they took place every 4 years, on the third year of each Olympiad, during the month of Boukation (late August) and under the supervision of the Hieromnemones.

Preparation

Preparations for the games began six months earlier. Nine citizens from Delphi, called Theoroi, were sent to all Greek cities to announce the beginning of the games in order to attract athletes, as well as to declare the Hierominia, the period of the Sacred Truce. The truce aimed at protecting not only the Theoroi and the athletes who were on the move, but also the temple of Apollo at Delphi. In case a city was involved in armed conflict or in robberies during that period, it was not only forbidden to enter the Sanctuary, but none of its citizens were allowed to participate at the games or to ask the Oracle for advice. At the same time, the truce allowed the Amphictyony to focus on preparing for the games, which included restorations for all structures of the Sanctuary, from the temples to the streets and fountains.

Equestrian and athletic competitions, carried out in nude, were introduced within the context of this reform; laurel wreaths were set as prizes made from the branches of the oldest laurel in Tempi (the sacred location of Aphrodite on Pineios river) by a ‘pais amphithales’ (Plutarch, Moralia 1136α), a boy whose parents were both alive. We do not have adequate information on the games’ program and duration. Information comes mostly from Pausanias (Phocis 7) and according to that source the Pythian Games lasted for 6-8 days, beginning from 586 B.C., and they took place at various venues within the Sacred Land of Delphi, whereas later on they were carried out at the stadium, the gymnasium, the theater, the hippodrome.

The program

The first three days comprised the religious ceremonies. The fourth day began with the musical competition, which in the first year involved singing and playing the guitar, playing the flute and singing accompanied by the flute in a mourning sound. The latter musical form was abolished by the second Pythian Games, as it was considered that lamenting songs were not becoming of such a celebration. Later on, painting competitions were introduced in the 5th c. B.C., dance competitions were added in the 4th c. B.C. and theater competitions were added in the Roman period, along with an increase in the duration of the musical competition.

On the penultimate day began the athletic competition, with four track sports (stadium, diaulos, dolichos and running with arms), wrestling, pugilism, pancratium and, finally, the pentathlon. These sports were established gradually in the course of the years.

The same thing occurred with the sports of the final day, which was dedicated to equestrian races; the latter gradually came to include: harness racing, synoris (a chariot drawn by two horses), chariot drawn by four horses and racing with a horse (without a chariot).

Pindar, the poet of the games

Pindar was born in 522 or in 518 B.C. at Kynos Kefales, a quarter of Thebes. He mentions that his birth coincided with a celebration of the Pythian Games (Vita Ambrosiana, frgm. 193), but it is not certain whether this was the Pythia of 522 or of 518 B.C. We do not know the date of his death. From dating his last surviving poem, researchers have reached the conclusion that he died around 446 B.C. He concluded his poetical training in Thebes as well as in Athens. Due to his reputation, his house became a sightseeing spot in ancient Thebes and Arrian mentions that Alexander the Great, as a token of honor for the poet, excluded this house from the destruction with which he punished the entire city in 335 B.C. (Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander 1.9.10).

Pindar worked on lyric poetry for choruses. The largest part of his surviving works is the Epinikia (‘celebrations of victory’). They are chorus songs sung in the homeland of the winner of the Games upon celebrating his success or even in the venue of the competition.

The Greek aristocracy of the first half of the 5th c. B.C., mostly the tyrants of Sicily and the conservative aristocracy of Aegina, were the main customers of the poet, as they considered him to be an exquisite panegyrist of the old threatened aristocratic values, particularly at a time of abrupt political change.

Praising the athletic success of the winner and his virtue, his family and his fortune is an occasion to celebrate aristocratic values. The winner’s laudation is reinforced by being intertwined with myth, which however challenges the understanding of the poem’s content and requires a well informed audience. The poet uses his work not only to speak of the victory won by his client and his family, but also to accentuate the family’s history and its connections all over Greece. In his Epinikia, Pindar includes sayings and aphorisms, often short and witty, interspersed in the poem as general remarks on the human existence, luck’s whims and, often, moralistic observations.

These 45 victorious hymns which have survived to this day mention the winners in the four most famous panhellenic athletic competitions and they are divided in four groups: celebrating victories in the Olympian, the Nemean, the Pythian and the Isthmian Games. The hymns celebrating victories in Pythian Games include 12 odes.

The Pythian games were conducted until 393/4 A.D., when they were banned by emperor Theodosius I.

Other festivals

Apart from the Pythian Games, the inscriptions offer information on other games taking place in Delphi, the Soteria. As attested by their names, these were games established on behalf of a salvation from certain enemies, namely none other than the Galatians, who had been defeated by the Aetolian League. The Soteria were initally celebrated annually, comprised musical, dancing and theatrical contests and the winners were offered money prizes. For several years it was the Amphictyony which was in charge of these Games, yet around 244 B.C. the Aetolians undertook the task themselves and reformed the Games. From then onwards the Games were taking place every five years, the participants contested in music, horseracing and athletic games fought in nude, whereas the prize was a laurel wreath. The Soteria probably stopped in the 1st century B.C, possibly due to the attack by Sulla in 86, which also caused the Pythian Games to stop for a while.

It seems that in the late 3d century and definitely from the 2nd century onwards the Amphictyons were willing to accept the establishment of new games, provided that those who suggested it could also finance the games. Thus, we know that games were taking place in honour of the Pergamene kings, namely the Attaleia and Eumeneia, which were however funded by the kings themselves. Even a rich citizen of Kalydon in Aetolia, Alkissipos, managed to get his own annual celebration established, namely the Alkessippeia, by donating a large sum of gold and silver around 182/1 B.C.; although this celebration did not include games, it seems that it comprised a ritual procession, a sacrifice and a public meal.

Apart from the standard Games and celebrations, there were also extraordinary ones, which were organized on the occasion of special events. This was the case of the Athenian Pythaids, on which the inscriptions of the Treasury of the Athenians are so eloquent. We know of four Pythaids which took place in the period 138-98 B.C. All four of them included a ritual procession from Athens to Delphi, headed by prominent citizens; they also included sacrifices and rituals and, finally, horse races and musical contests. The inscriptions with the hymns of Apollo which have been preserved on the southern wall of the Treasury of the Athenians were carved exactly on the occasion of these Pythaids.

The Delphic Festivals

In the 20th century, the poet Angelos Sikelianos, who delved into the ancient Greek spirit, conceived the idea of creating in Delphi a universal intellectual nucleus, capable of reconciliating the world’s nations (the «Delphic Idea»). To that end, Sikelianos, with the assistance and financial help of his wife, Eva Palmer-Sikelianos, lectured extensively and published studies and articles. At the same time, he organized the «Delphic Festivals» at Delphi. Apart from staging performances of ancient plays, the «Delphic Idea» included the «Delphic Association», a worldwide association for the fraternization of the nations and the «Delphic University», which aspired to unify the traditions of all countries into one ecumenical myth.

The first Delphic Festival began on the 9th of May 1927 and lasted three days. It included ancient drama plays performed by amateur actors (Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus), athletic competitions in the nude, concerts of byzantine music, lectures and folk art exhibitions. The festival was repeated on the 1st of May 1930, with a performance of Aeschylus’ tragedy The Suppliants. The interpretation of the tragedy aspired to a revival of ancient drama teaching, but the accompanying music was composed in the Byzantine style. The costumes were created by Eva Sikelianos herself, based on folk art models.

The events were attended by numerous scholars, artists and journalists from all over the world. The invitees responded with enthusiastic comments and articles although some criticism was expressed as well.

Despite the fact that the Delphic Festivals greatly promoted tourism and the diffusion of folk art in Greece and abroad, they were discontinued, because the Sikelianos couple, who had undertaken almost all of the expenses, was financially drained. Angelos Sikelianos had refused any state subvention. However, this first attempt at resuscitation of ancient drama within archaeological sites instigated further similar efforts at a later date, such as the, now world-famous, Festival of Epidaurus, which was inaugurated in 1955.

The European Cultural Center of Delphi

In certain ways, the vision of Angelos Sikelianos has survived in the modern “European Cultural Center of Delphi”, which was founded in 1977 at the instigation of Konstantinos Karamanlis, prime minister of Greece at the time. According to its statute, the E.C.C.D aspires to «develop the common cultural elements which unite the peoples of Europe». The E.C.C.D organizes or hosts a number of cultural activities and events as well as seminars, conferences and educational programmes related to ancient Greek culture as well as to the idea of peace and fraternity among the nations. Integral part of the E.C.C.D. is the Museum of the Delphic Festivals, housed in the home of Angelos and Eva Sikelianos at Delphi. It includes photographic and printed material from the Delphic Festivals, costumes from the ancient drama performances, the famous loom belonging to Eva Sikelianos, manuscripts by the poet and other objects.

International Delphic Council

In 1983, Mr. J. Christian Β. Kirsch established the “Musica Magna International” at Munich, aiming at restoring the Delphic Festivals. This initiative was backed by Federico Mayor Zaragoza, Director-General of UNESCO. In 1994, 100 years after the revival of the Olympic Games, representatives from 20 nations and from all 5 continents responded to the invitation of the founder of the contemporary Delphic movement, during the inaugural conference of the “International Delphic Council” (IDC) in Berlin. The establishing assembly of the International Delphic Council took place on the 15th of December 1994 at the Schoenhausen Castle in Berlin.

The IDC is the supreme authority of the Delphic Movement. Its members are the National Delphic Councils (NDC) as well as VIPs from the arts, culture, education, finance, associations and institutions. The IDC Administrative Committee is the Executive Board. Following the model of Classical antiquity, it is called Amphictyony and it is composed of 12 elected members. The most important duty of the IDC is to reinforce the Delphic Movement and to organize international Delphic Competitions (some of which are addressed to Youth), in order to contribute to the understanding between peoples and cultures worldwide. The competition includes the following categories: Musical Arts, Visual Arts, Literature, Fine Arts, Social Arts, Architecture & Ecology. Winners receive a medal, a lyre and a laurel wreath.

The Delphic landscape

The archaeological site of Delphi and its region, surrounded by the mountains of Parnassus, Giona and Kirphe, and stretching mainly among the settlements of Amphissa, Arachova, Delphi, Itea, Kirra, Agios Georgios, Agios Konstantinos and Sernikaki, constitutes a landscape of exquisite beauty, outstanding world-wide historical value and artistic importance. No wonder that Delphi has been included in UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Besides the actual monuments of the archaeological site of Delphi, the region comprises a number of monuments and sites, dating from the Prehistoric to the Modern period; all of them stand out for their archaeological, historical aesthetic and social value which, along with the surrounding rural and forest regions, the so-called Delphic Landscape, constitute a testimony to the history of the region. Together they have contributed greatly to the formation of an educational and spiritual center which represents eternal human values.

For the protection of this region, which was considered “sacred land” in antiquity and was offered to the god Apollo, the Greek State has designated zones of protection. These zones aim at maintaining “the unique value of the monument which is born of the harmony among the ruins of the sanctuary and the unscathed environment (…). One has to let one’s gaze wander from the silvery sea of the olive trees to the valley of Pleistos and to the sparkling sea of the Gulf of Itea, in order to realize that the role of Delphi was to unite islanders and landlubbers in joint rituals”, to quote the report of ICOMOS for the enlisting of Delphi in the World Heritage List.

Delphi is built at the feet of the imposing Phaedriades, two enormous cliffs which form part of the south side of Mt. Parnassus. They command a narrow plateau, which formed –possibly – the only passageway leading from Attica and Boeotia to the heart of Phocis and Western Greece. Fossil examination has proved that the rocks belong to the Jurassic and the Cretaceous period. The softer soils are mostly limestone and schist. The schist plaques present faults, as is evident on the spot where the temple of Apollo was built. This resulted in making them vulnerable to earthquakes as well as to corrosion of the earth. Although they were erected on a mountainous and rocky area, the buildings of Delphi suffered damage from earthquakes several times in their long history and were often almost entirely destroyed. Corrosion of the ground, on the other hand, as well as land-sliding of the plaques cause rock-falls, such as the one which destroyed the first poros stone temple at Marmaria. Finally, the constant sliding of the earth under the ancient monuments, particularly in steep areas, like the one on which the ancient theatre of Delphi is built, presents a major threat.

MUSEUM OF DELPHI